Backstory is an object-focused methodology for teaching professional thinking in Performance Design developed by Rebecca Pride, Course Leader, School of Performance, Arts University Bournemouth. This text is an extract from a paper she gave at the Association of Courses in Theatre Design Symposium, 2012. It explores how she uses MoDiP's collection to encourage designer thinking amongst students studying for a BA (Hons) in Costume for Performance.

My rationale for the Backstory workshops was twofold. I wanted to test professional thinking and help the cohort to understand their responsibility as designers. The backstory workshops are named after the name given by actors who work with the ubiquitous Stanivslaski method, as a rationale for their own character development. Hatchuel states:

The Stanislavski method, notably concentrates on the psychology of the role, and consists of seeking in the play how the characters describe themselves or how they are described by the other characters. The aim is to get a global and unified image of their personalities and, therefore, to reach the truth of the part.

Hatchuel, S. (2004). Shakespeare from Stage to Screen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p.133.

This is what Kenneth Branagh called the "backstory" in his introduction to his screenplay for Much Ado about Nothing, (2003, p.xi). He states:

The audience won't know specifically my off- screen history for Benedict - his upbringing, his family, his likes and dislikes - but I hope that with this history firmly in my head, they will at least intuit part of it, feel a depth of character beyond what he says and does.

The words 'Truth' and 'Intuit' are of course intrinsic here. If designers could also appreciate 'the backstory' of their own set and costume design, then surely they would become better designers, with a qualitative improvement in their learning and designing?

I borrowed various objects and garments from MoDiP. It offers a diverse collection of 20th and 21st century items of everyday design including fashion and costume, printed ephemera, packaging and domestic design. I chose the items for my workshop relatively randomly: a pink dress, a handbag, a pair of 1940's shoes, some early twentieth century nightdresses, a green 1960's dress and an evening dress with stole.

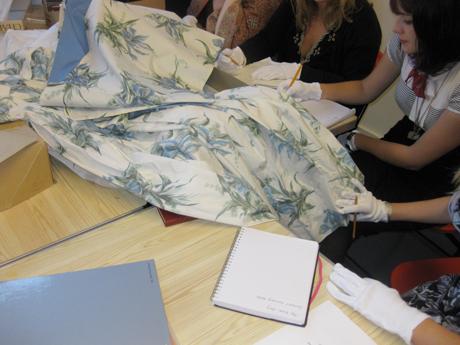

The workshop took the following form. I distributed paper, pencils and white gloves to the students, as obviously for items borrowed from a museum it is vital to protect the artefacts from damage. The students were divided into pairs and all took paper and each group was given a box to open. I asked the students to look carefully at the items - the fabric quality and design, the typefaces on the labelling and write a description of the sort of character that might wear or own the artefact in their box and then to each draw their characters and confidently present their findings in a group setting.

I wanted the students to:

- engage in creative thinking about the history / context / meaning of design choices

- build a 'Backstory' for the items they were looking at

- discuss aesthetic consideration of design and fabric

- draw a character that might wear their item

- understand that all choices that a designer makes are important and must present the truth embodied in that character or element

- develop presentation techniques in a group setting

It was remarkable how well the students responded to the session. They developed very accurate responses to the garments. The library held documentation that supported some of the items - letters and photographs that described the actual Backstory of the clothing. It was very surprising how accurately the students' detective work was when I eventually revealed to them the 'truth' about the clothes. Afterwards the students reflected that they felt more creative, imaginative and good at problem solving. They felt they had learnt how even the smallest detail of a costume could have a significant effect on the meaning for the audience. After thinking about it in such a focused way they reported that they were shocked by this sudden strong sense of contextual understanding.

The written feedback responses to the session were particularly encouraging.

One student wrote:

I think it's important that you can clearly put across your design ideas regardless of drawing ability. I found it interesting to look at the garments in detail, and clearly inspect it to try and figure out its backstory. It made me think about the person who it belonged to, and it will help me in my designs when creating a backstory for my characters.

This is the level of understanding I am aiming to achieve with the students I teach. The intuitive understanding of my students and their positive responses to the session was encouraging. This is learning on a deeper level than a simple behaviourist, didactical teaching of period costume history. I have continued with the Backstory sessions. Indeed I have subsequently developed a fabric backstory session with students selecting fabrics I provide them with and drawing the sort of costume that might be made/created with the specific fabrics. I have noted that this is a skill that all experienced designers possess, but that for students this can be more difficult - practising naturally develops the skill to understand the meaning and power of different fabrics.

MoDIP holds thousands of artefacts most of which are made from plastic and I have borrowed many of them - radios, hairbrushes, a brown 1970's Trimphone, an Alessi kettle and even a set of Edwardian fish knives. The student theatre designers can perform the same task - looking, thinking and drawing the characters that spring forth from these items. It's simple, but developing 'the Backstory' appears to reinforce a sense of 'Designer thinking' that is deep and lasting.